The new age of armed groups in the Middle East

A story of fragmentation – from the 2011 revolts to the Salafist group HTS

An ecosystem of armed groups emerged in the Middle East during the Arab revolts of 2011. This conglomerate of unstable forces is led by warlords, some of whom receive foreign subsidies, and others who finance themselves through predation and terror.

At the height of the Syrian revolution, 5,546 armed groups were identified on the front lines segmenting the country.“Syria Contrywide Conflict, Report 3”, The Carter Center , March 14, 2014. In Libya, the estimate of 110 fighting entitiesLipika Majumdar Roy Choudhury (coord.), UN experts’ report on Libya, United Nations, December 9, 2019. does not include the less damaging cells that Tripoli is still trying to register.Sami Zaptia, “Ministry of Interior decrees to categorize and DDR militias”, www.libyaherald.com, September 16, 2020. Iraq has an approximate average of 180 groups – adding up the organizations that are created annuallyTramer Badawi, “Iraq’s Resurgent Paramilitaries”, Carnegie, 2021. and substracting those that dissolve, not to mention the facade groups whose objective is to “make noise” on social networks in order to thwart the surveillance of intelligence agencies.

Are they non-state groups? Anti-system? Supra-national? Pro-state? The only thing certain is their ability to establish themselves in failed states, with no possibility for these to defeat them, except by the commitment of disproportionate military forces in highly complex regions. In the space of a decade, they have become the main providers of fighters in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya. Their sudden emergence has fragmented the Arab protest scene and marginalized traditional political parties (Baath, Istiqlâl) by establishing new lines of force.

This phenomenon stems from a long continuum of historical setbacks that have progressively affected the paradigm of the nation-state in the Arab world. The old concept of the national banner aggregating a mosaic of populations has been discredited. The West had promised emancipation and influence to those who would conform to this model. It has not been the case.

At least three fundamentals have been affected.

- The national force

After colonization, many Arab states founded their authority on military institutions that were supposed to symbolize national unity. Decision-making centralism brought together clans, tribes and ethnic groups who discovered a common border. A climate of distrust quickly developed between the citizen, suspected of disloyalty, and the soldier – the weak link in a military without panache. After three defeats against Israel and two Gulf wars, the Arab revolts of 2011 finally shattered the dream of a force protecting the people. Almost all of the regimes threatened by the revolutionary fever (Libya, Syria, Yemen) shot at the demonstrators with live ammunition.

- The human brotherhood

While Arab peoples fervently express the wish for unity (tawhid), few regimes embody the ideal city of Al-FarabiAl-Farabi, Traité des habitants de la cité idéale, Vrin, 1990.. For a long time the Lebanese Constitution legislating communal co-existence was an example. However, the 1975 civil war shattered this concept of a plural nation. Beirut became a capital where political and religious balances of power and commercial interests were negotiated. Militias entered the game, including Hezbollah, whose inexorable rise is undermining governance based on brotherhood of religious faiths. The Lebanese dream is over.

- The political representation

As 2011 marked the fall of post-colonial regimes, the revolutionary dynamic has forced Arab peoples to imagine a future other than the simple rejection of totalitarianism. In the absence of ideological homogeneity, a superposition of religious, political and ethnic spheres has redrawn the maps. Libya has split in two, Syria in four.Northwest: Hayaht Tharir Al-Sham (HTS). Northeast: Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Southwest: Deraa, the cradle of the protest. Center, governmental area: Syrian National Army and pro-Damascus militias. Iraq has become federalized and Yemen is fragmented. Confidence broke down between the political formations recognized by the authorities and the population, which feels abandoned, with no other representation than improvised armed groups, poorly equipped and poorly coordinated, whose primary objective was not necessarily political involvement, but the defense of a village community or a neighborhood trapped in the turmoil of the revolution.

The armed groups concluded that the nation-state was inadequate because of the breakdown of its three fundamentals: national strength, human brotherhood and political representation. The Arab regimes were said to be the result of a trade in sins (tijarat alkhatiya), that is, the maintenance of their privileges in exchange for the renunciation of true independence, which would have consisted of living their Arabness and faith to the fullest, and not being an ersatz of the former colonial powers.

Conflicting analyses

Several hundred armed groups now form an ecosystem regenerated by an uninterrupted flow of recruits. For the West, the beginning of the fragmentation dates to the defeat of Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. Driven out by American bombs, Bin Laden abandoned his top-down chain of command and dispersed his men to the front lines of a jihad that has become multi-polar.

A process of fragmentation then began, followed by the caliphal adventure of the Islamic State group, which galvanized new conflict zones in Africa (ISWAP, ISCAP) and Asia (IS-K), also gene-rating segmentations. While counterterrorism has achieved clear successes, these have had the effect of dispersing the enemy. Paradoxically, the more weakened and disorganized an armed group is, the more difficult it is to defeat it completely.

The perception in the Middle East is different. The group structure is seen as inherent in the Arab political DNA, which Ibn Khaldun theorizes as al-Asabiyyah to refer to the martial feeling of belonging to a human collective. The idea that a group assumes regalian functions (security, politics) has long been accepted, long before the colonists undertook a tedious classification of the “natives” and finally settled on the following formula: an alliance in its purest form – group, clan, tribe – is a state without a state.Philip S. Khoury, Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920-1945, Princeton University Press, 1989.

The armed group is based on fighting solidarity and the convergence of immediate interests. It is not conceived as a regressive structure, but rather as the desirable balance point between the present world and the archetypal moment of prophetic revelation in the seventh century when Muhammad established tribal lordshipJacqueline Chaabi, Le seigneur des tribus, l’islam de Mahomet, Éditions du CNRS, 2013. and engaged in wars of apostasy (ḥurūb al-ridda). This is an ancient radical idea, according to which the Muslim community is forced to relive similar events until the divine law is established on Earth. Yesterday it was Arab tribes protecting the messenger Muhammad. Today, it is armed groups protecting Islam from the existential threat of the infidels.

The groups subvert the meaning of the word tribe, originally “community of traditional va-lues”, to include a revivalist dimension. An allegorical link is made between the activist and his understanding of the religious narrative. In prophetic times, Arab forces practised surge. Mobility was favored, and the number of men rarely exceeded a few dozen. This is the model for today’s fighters. This reasoning also applies to the great Arab empires. When the vizier worked to ensure the political cohesion of a territory, the remote populations benefited from a quasi-autonomy as long as the taxes were paid. This pattern – a strong state, a weak country – is a forerunner of the current situation. In Syria, for example, Damascus is a strong and authoritarian regime that governs a weak country.

The Arab regimes are the first to perceive the threat of individuals in search of an “entre-soi”, reminiscent of the batinites of yore (secret societies). These places have always been propitious to theology makers that the essayist Boualem Sansal described as “versatile and opportunistic [who] gather at will in the immense tree of Islam”.Boualem Sansal, Gouverner au nom d’Allah. Islamisation et soif de pouvoir dans le monde arabe, Gallimard, 2016.

At the height of his power in the 1970s, Gaddafi “retribalized” Libya by creating Popular and Social Commands (PSCs) in order to re-establish organic links between the capital and the chiefdoms. In this way, he sought to counteract the growing influence of the ulemas, who considered his jamahiriyya to be blasphemous. Saddam Hussein initiated a policy known as neo-tribal. After banning any public mention of the country’s tribal sediments, he made a U-turn and decided to regain control of traditional governance structures. For its part, Syria has chosen to set up local councils. Their purpose is to bring back into the national arena the initiatives, if not of self-management, of defiance towards the discredited regime.

It should be noted that neither Libya, nor Iraq, nor Syria have escaped the post-2011 civil wars. The reclamation of the tools of popular governance came late, without a will to establish a new mode of peaceful coexistence.

Emergence and profusion

The unexpected impact of the 2011 revolts was a repositioning of al-Asabiyyah at the heart of the protest dynamic. People allied themselves out of survival instincts along filial, political, or religious affinities. Groups emerged in the face of growing insecurity, like in Zamalka, a small Syrian town battered by a series of attacks in the summer of 2012. Young people took up arms to protect their community. Two Islamist groups operating in the area offered to help them. They indoctrinated them and took control of this initially secular self-defense

initiative.

Rather than restoring the authority of the state and asserting its regal power, Arab regimes have responded to the proliferation of groups with a further proliferation of groups. The Sy-rian regime created the National Defence Forces, which gathered dozens of trained militias and criminal gangs (chabiha). Prime Minister Al-Maliki’s Iraq entrusted the Ministry of the Interior with the formation of the Popular Mobilization Units, which institutionalized the milicization of the country – 12,000 men who obtained the status of civil servants in 2015 while retaining their freedom of initiative.

The phenomenon extended to regional powers. NATO member Turkey has formed a so-called “national army” of some 40 Salafist groups to defend Ankara’s interests in northern Syria. Iran has committed $700 million a year to support a swarm of fighting entities loyal to the Islamic revolution.“Iran Action Group”, U.S. Department of State, 2020. The West has adapted. In its quest for a victory over Damascus, it supported the Syrian resistance by supplying Syrian armed groups identified as capable of fighting against the regime’s forces with weapons, including TOW missiles; among them Kata’eb Thuwar Al-Sham, Forqat 69 Quwwat AlKhassa or Tajamuu Suqour Al-Ghab.

Thus, Arab countries where military institutions dominated public life before 2011 began to fragment. Defense doctrines were then correlated with weapons acquisition programs and the development of capabilities (tanks, aviation, artillery). It was unimaginable that the choice of weapons would one day be left to civilian groups. In the early days of the Syrian revolution, the army had 325,000 soldiers and a reserve of 314,000 men.The Military Balance 2010, IISS. The use of auxiliary forces was not necessary from a strictly operational point of view.

Did the Arab national armies fail? Were they so overwhelmed that they adopted the modus operandi of the revolutionaries in the hope of defeating them? Remember that the disavowed regimes had to urgently identify their opponents. Considering the desertions of soldiers (Syria) and the lack of combativeness (Iraq), working with what existed was certainly the most immediate and obvious solution: neutralizing groups by using other groups. The second explanation has to do with the human factor, with the resolutely fratricidal nature of the conflicts. Aggressors and preys instinctively shared a strategic culture, which “refers to the traditions of a nation, to its values, attitudes, behavioral models, habits, symbols”, Hervé Coutau-Bégarie wrote.Keith Krause, Culture and Security. Multilateralism, Arms Control and Security Building, Frank Cass, 1999, in Jean-Marc de Giuli, “Des cultures stratégiques”, Inflexions, 2009.

An attempt to classify the armed groups

The empirical approach to this ecosystem is often parasitized by the use of the word “terrorism” to distinguish, on the one hand, groups that can be acceptable from, on the other hand, terrorist groups that cannot be frequented.

If we examine the context of the use of this powerful determinant, we find that it is constantly being transgressed.Although the word “terrorism” is subject to multiple definitions, it is established that the does not denote an ideology, but a modus operandi: the disproportionate striking of an enemy narrative to affect its resilience. Turkey backs groups (Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham, HTS) that its own laws consider “terrorist”. Moscow maintains relations with Hamas, whose military wing is on its blacklist of unfriendly visitors. The European Union has pledged 1 billion euros to the Taliban, which is co-led by the Haqqani Shura linked to Al-Qaeda. The United States uses this categorization as leverage. The Houthis were removed from the list of terrorist organizations as a sign of goodwill from President Biden before being threatened of being put back on the list due to the Yemeni crisis. As for the decision to keep the Iranian Pasdaran on the list, it has become a subparagraph of the negotiation with Tehran.

Since categorizing armed groups according to “terror” does not stand up to Realpolitik, another option is to use the territorial determinant to differentiate: 1) a group defending a transnational ideology; 2) a territorialized group that does not manifest a desire for absolute control; 3) a group driven by a governance project. This approach is coherent with Western thinking, whose power strategies are built on territorial possession. However, armed groups do not develop this type of argument, except in an allegorical way “Land, kingdom of God”. Their objectives are usually the overthrow of a regime, the establishment of a religious law, or the elimination of infidels.

Another method would be to categorize the firepower of armed groups in order to assess their capacity to cause harm and spread.

- The skirmisher group

Equipped with light weapons, its logistical deficiencies limit its action to a narrow geo-graphy. These include lead groups created by one or more military operations rooms to deal with specific objectives.A military operations room is a pooling of operational resources.

- The structured group

Equipped with rocket launchers and a fleet of vehicles, its leaders are able to establish a strategy. It organizes the mobility of its men and negotiates alliances with other groups.

- The proto-state group

Structured in combat units, it disposes of regular sources of funding and supply lines for weapons. Salaries are paid, as well as pensions to the families of those killed. The group exercises total or partial territorial control.

- The meta group

The entity pretends to exercise the four powers: religious, political, military and socio-economic. It levies taxes, provides services (water, electricity, telephone) and ensures security for – or martyrizes – sedentary populations.

This pyramidal classification proceeds from a progression of less to more. Here again, the approach is underpinned by Western thought. For armed groups, it would be more appropriate to conceive of an increment from the impure to the pure, in order to appreciate the transcendental value of the struggle engaged.

For a right use of segmentation

Although the Islamic fighter wants to bring forth the universal man (alinsan al-kamilThe universal man: al-insan al-kamil. Also called the “good individual” (takwin al-fard al-gayyid) or the “great man” (al-insan alkabir).), the immaculate worshipper of God, the concept of fragmentation is intellectually accepted. In Afghanistan, the recruits who came to fight the Soviets and found the third way, the spectral jihad, were grouped together on their arrival by country of origin (Egypt, Algeria, Sudan). Al-Qaeda recruitment in Yemen incorporates the Kabail/Bakil antagonism that dates back to the genealogy of the Queen of Sheba. The Islamic State group allocates dedicated units to its international volunteers. As for the Syrian civil war, it produces its share of so-called foreign groups, some still operating: Tawhid and Jihad (Uzbek), Jaich Al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar (Caucasus), Uqba Bin Farqad (Azerbaijan).

As this segmentation is admitted by the groups themselves, and not perceived as a degene-rative after-effect of discord, the ecosystem of armed groups can be analyzed in terms of what divides them.

The split of an armed group or the alliance of two groups is decided during the shuras (councils). Composed of a dozen men, often less, these deliberation forums issue opinions that support or reject decisions that are binding on the group. The institution emanates from the prophetic narrative, when Mohamed consulted his companions before ordering. It recalls the primacy of the community over the individual and the existence of mechanisms of deconflictionErnest Gellner, Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East, Tauris, 1991. and conciliation (sulha) to regulate human tensions. If division is deplored as contravening the pact of oneness willed by God, it is nevertheless read as inherent to human discord (fitna); a proving ground.

The human factor

Although each group has a specific genesis and operational context, the study of a particular case allows for the identification of the matrix function of the human factor in this fragmentation/reunification process.

Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) is part of the neo-Islamist lineage which, without compromising on the Salafist exegesis, bases its action on the general interest (al-masa’il al-mursala). It does not theorize paroxysmal violence on the grounds that it was the error of a period. It engaged in a polarity inversion after having been a major actor in the fragmentation of northwestern Syria – fratricidal wars and doctrinal ruptures.

Its reasoning is as follows:

- Fighting against the division of the Ummah is the spiritual path of every believer. Group solidarity (al-Asabiyyah) is the goal.

- The fragmentation of the world is not written in the Qur’an. The sharia commands the coexistence of people and requires the prevention of arbitrariness (sadd al-dharî’a).

- The uninterrupted recruitment of volunteers into the groups is a testimony to the vibrancy of Salafism despite the loss of life in battle and the defeats. Unifying this movement will allow it to gain a seat at the negotiating table.

Abu Mohammad al-Julani, leader of the HTS group and figure of a generation of Syrians that nothing predestined to the civil warAl-Julani has long maintained the mystery of his identity. When the American armed forces registered him at the Bucca prison camp during the Iraq war, he called himself Osama Al-Absi Al-Wahdi, an alias used in clandestine life. His identity document says he was born in Ash-Shukheil, district of Deir Ezzor (Syria). After a decade of rumors, the Salafist leader consented to reveal his civil status. His name is Ahmed Hussein Al-Shara. He is Sy-rian, born in 1982 in the Gulf during a family trip. His paternal family is from Faiq, a village located on the Golan Heights that came under Israeli control after the Six Day War; hence the nickname Al-Joulani. Pronounced in Arabic, Joulani evokes the sound of the name Golan., is the one who presents himself today as the architect of the re-sedimentation of the rebel forces. He grew up in the wealthy district of Mazzeh, in Damascus, with his five brothers and sisters. His father, a professor of economics, educated him without excessive religiosity.Al-Julani’s father travelled the Arab world as an energy specialist. He was spotted by the Syrian Prime Minister’s office, where he ended his career. In anticipation of his old age, he set up a family business, a store called Mini Market ash-Sharaa, near the Al-Akram mosque, where Al-Julani, then a university student, came to help him. After the shock of the 2001 attacks, he left to fight in Iraq in Al-Zarqaoui’s group, renowned for its barbarity. He was arrested and incarcerated in the Bucca camp, where the future leaders of the Islamic State group were already located.

In prison, Al-Julani wrote a radical manifesto, some fifty pages entitled “The Nosra Front for the People of the Levant”.The first draft of the title was “The Nosra Front for the People of the Levant from the Levant Mojahedin on the Battlefields of Jihad”. Al-Julani now alleges that this text has been misplaced. Paradoxically, this text drove him to high responsibilities in terrorist organizations (ISIL, Al-Qaeda) from which he wanted to free himself. He founded an armed group whose name changes according to the balance of power on the ground. He makes and breaks alliances, attacks his rivals and chases away foreign fighters who take refuge in his territory. His strategy for breaking away is questionable. So is his aplomb. Al-Julani does not hesitate to dissociate himself from groups at the height of their power.

There are several explanations for this:

- Each breakaway distances Al-Julani from a model he considers ineffective: the armed terrorist group. The break is not seen as a failure, but as a qualitative step toward the Islamic ideal. It is a disengagement maneuver.

- Radical islamism understands the structuring of a group as intrinsically non-permanent, without real importance. HTS does not hesitate to evoke the hypothesis of its own dissolution.Sacha Al Alou, “التفكيك واحتماالت المستقبل سؤال“.. الشام تحرير هيئة”, “Hayat Tharir al Sham, the question of the future and the possibilities of dismantling”, www.alsouria.net, February 17, 2020. ISIL writes: “O soldiers of groups and organizations, know that after the establishment of the caliphate, the legitimacy of your groups will be empty”.Cole Bunzel, “From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State”, Center for Middle East Policy, Brookings, 2015.

- The ruptures that mark out Al-Julani’s journey are what the philosopher Ernst Bloch calls “the concrete utopia”Ernest Bloch, L’Esprit de l’utopie, Gallimard, 1977. of a Salafist leader who becomes what he dreamed of being, without any compromise with others.

Al-Julani’s approach correlates two contradictory ideas. The acceptance of segmentation as long as it is tactical and ad hoc. The requirement of oneness (tawhid), a divine instruction that works for the cohesion of the Ummah, thus the aggregation of groups. In this, he is inspired by Muhammad, who thought of Islam as an alliance of peoples, a corpus that does not interfere in the organization of tribes as long as they respect the divine law.

The Salafist leader is moving away from the bureaucratic model of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is fussy and inefficient when it comes to exercising power. He distances himself from the overly pyramidal organizational structures of al-Qaeda and ISIL, which have never prevented territorial defeats. He rejects the chains of command improvised by armed groups du-ring the civil war. See the following model:

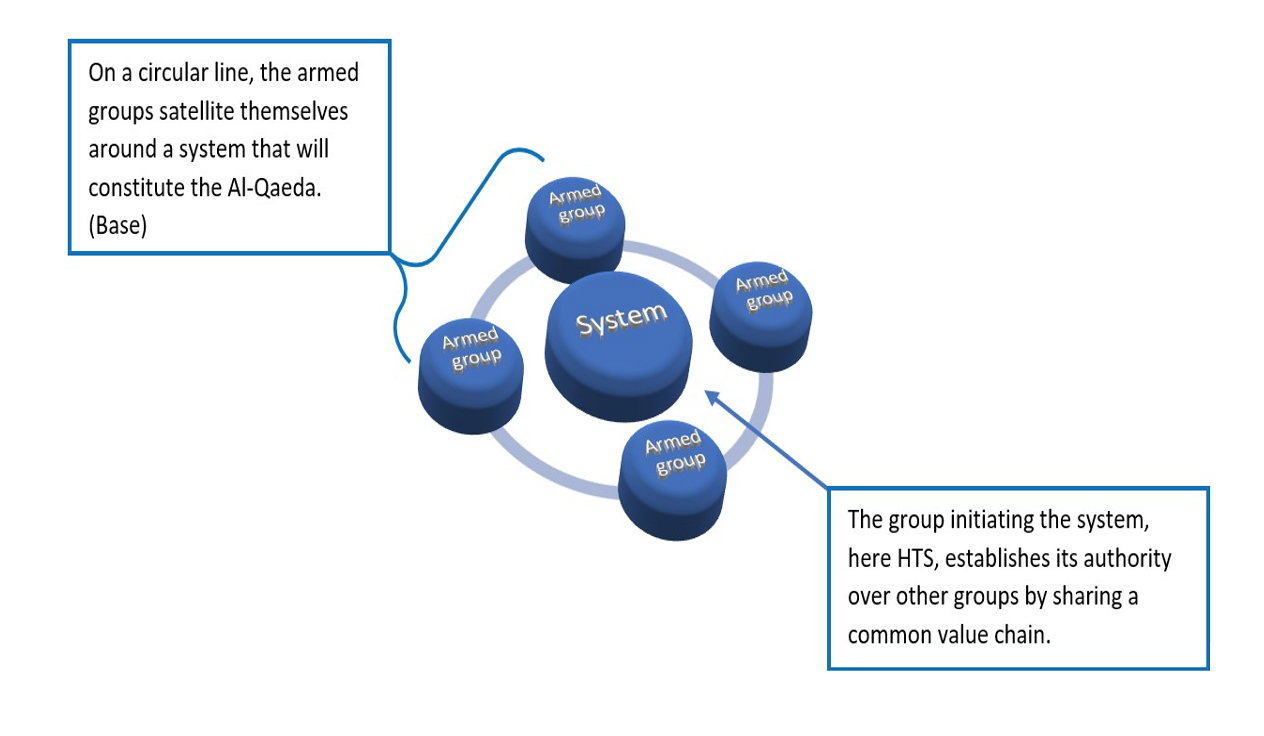

This organizational structure was not deemed convincing by the armed groups. Al-Julani preferred to follow in the footsteps of Abu Mus’ab Al-Suri, a former member of Al-Qaeda’s Command Council and the author of a seminal book of the radical underground: The Call for Global Islamic Resistance. This text asserts the predomi-nance of a system over an organization. It posits that the “system” shares a military objective, a name, a doctrine, and a training program at the heart of the jihad. It is the base, which translates into Al-Qaeda, the foundation, the “common model for a human community”.Abhijnan Rej, “The Strategist: How Abu Mus’ab al-Suri Inspired ISIS”, ORF, August 3, 2016. Around him, armed groups respond to the call. The system unites scattered forces, so that the alliance is not just a verbal agreement between leaders, but a sharing of common values.

Since 2020, Al-Julani has taken advantage of the stabilization of the front lines to make an organizational change. Civilian actors have joined the circular line (see diagram above), previously monopolized by the groups. A Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) administers the lives of people in the rebel areas: health, education, economy. A Ministry of Defense is being formed to develop a comprehensive approach to security issues.Among the questions: should they adopt the military gradation (corporal, sergeant, warrant officer) and give up the Islamic one (shahid, emir, sheikh)?

The HTS executive is organized around commanders loyal to Al-Julani who fight against the dispersion of groups by standardizing the training of men (military college) with the support of organizations such as the General Security Agency. HTS maintains relations with components outside its system, unlike ISIL which wanted to impose a single model, applicable as is and without compromise. He tried to contain the rivalries between clans“ي ريف الحسكة ي حادثة ثأر تشعل اشتباكات عشائرية بـ رأس الع ف ” [Revenge incident sparks clan clashes in ‘Ras al-Ain’ in Hasaka countryside], www.syria.tv, May 25, 2022. and encourage mergers.“ للتحرير ثائرون هيئة ”مع“ الشام أحرار ”من عنرص 1700 اندماج.. حلب ريف” [Aleppo campaign; 1700 members of Ahrar alSham merged with Revolutionaries for Liberation], www.enabbaladi.net, May 25, 2022. His emissaries held dialogues with the tribes and religious minorities. Draft agreements were drawn up.

Unity seems to be a real and serious goal, but the methods of persuasion are often those of domination. New lines of tension are emerging. The more HTS normalizes its modus operandi, the more it attracts the animosity of the extremist gangs. Significantly, the disputes are about tactics, not doctrinal content. Given that Al-Julani is a former member of Al-Qaeda and ISIL, the authenticity of his motivation is not in doubt. The Salafist leader lauded the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan, another fragmented movement capable of aggregating against an adversary. His closest associates offered their condolences after Al-Qaeda’s leader, Al-Zawahiri, was eliminated by an American strike.

This decision-making geography of Al-Julani is indicative of an Islamist tendency that aspires to rational governance. It wants to shift from being a terrorist organization to being an aggregator of rebels. Nevertheless, its command structure is heavily influenced by the insurgency model.

The organizational chart shows the prevalence of military profiles within HTS. Jurists who support the Salafist cause and personalities from civil society constitute a minority. The Salafist leader may have made significant gestures, such as reaching out to the Christians of Idleb, dismissing radical members of the shura, and saying that he is renouncing the revolution to “build a Sunni entity”,“ فكرة ً ي الغيا ”الثورة“..“ يم الجوالن“: “ إسال رشوعنا بناء كيان س ن ي م” [Cancelling the idea of revolution, Al-Joulani: “Our project is to build a Sunni Islamic entity”], www.alsouria.net, July 16, 2020. but will this be enough to impose his strategy of openness? If the strategy fails it will reinforce the thesis that the Islamist movement is fatally flawed, unable to grow except through internal quarrels and ideological schisms, forever striving for the – impossible? – balance that must be established between arbitration (hukûma), sacred law (fiqh) and power (hukm).

Order the chaos

In the end, the proliferation of armed groups in the Middle East stems from a sum of exogenous factors: the revivalism of populations wishing to live what the West considers archaic: group, tribe, clan; a desire to appropriate the terms of societal debate and the rejection of official institutions (party, union, state) in the hope of founding a qawn, “nation” in the tribal acceptance of the meaning or dawla, a “state” in terms of the caliphal perception.

The 2011 revolts generated an unexpected shock wave, with no real ideological homogeneity. If we analyze it in time, we can see that the groups’ objective was less the conquest of political power – did they have the means? – but rather the will to embody a strict and literal Salafism. This new generation of rebels, some speak of a rebellocracy,Ana Arjona, “Civilian Resistance to Rebel Governance”, HiCN, February, 2014. remains a challenge to the world order by its multiplicity and its ability to mutate. A senior European official agrees: it has become increasingly difficult to “find one’s way around”Confidential interview, 2022. this jumble of companies (sariyya), battalions (katiba), regiments (fawj), brigades (liwa), divisions (firqa) and armies (jaysh); the titles of which rarely correspond to the number of troops engaged in combat.

The foreign policies of Iran, Turkey and Syria are now inextricably linked to these groups, which act as auxiliary forces, actors of influence or metastatic entities projected onto the rear lines of an enemy. They are integrated in the array of forces deployed as “secular arms” or “nerve endings”. The major powers have developed skills in this area. The Russian military has recently participated in the creation of a military operations room called North Thunder-bolt, alongside Iranian officers, SDF and a Baath (regime forces) unit. The 600-strong force is based in the Syrian village of Hardatinin. U.S. forces at Al-Tanf base conducted a training exercise this summer with the Maghawir Al-Thawra armed group, which recently acquired M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) missiles.

The established presence of armed groups raises questions.

- Regional powers are developing hard power strategies that consist of financing, arming and sometimes even framing swarms of fighting entities that are fragmented and therefore difficult to apprehend. The most explicit case is that of Tehran with its tactic of spreading pro-Iranian militias throughout the Middle East.

- The use of armed groups involves the responsibility of states. The Geneva Convention of 1949 places on an equal footing “those who have committed [a crime] or [those who have] ordered it to be committed”.

- In the name of the legitimacy acquired in the fight against ISIL, the groups are deman-ding, if not the maintenance of their prerogatives, at least guarantees of subsistence – salaries, weapons, and logistics. The Arab regimes concerned feigned indignation but de facto give in to these demands, especially Iraq. The implementation of DDR (disarmament, demobilization and reintegration) programs seems totally unrealistic at this point. Yet this would be the minimum requirement for any peace process.

There remains the human factor, the design of the men and women who have engaged in the revolt for good or bad reasons. We are certainly in the presence of these “united violences” evoked by Ibn Khaldun, the founding father of Arab sociology, to depict a human fraternity eager to found a new order. Armed groups follow a similar dynamic, torn between the desire for emancipation and the complex game of regional alliances; condemned to live what Aron called: the impossible peace.Raymond Aron, Le grand schisme, Gallimard, 1948.

The new age of armed groups in the Middle East

Note de la FRS n°40/2022

Pierre Boussel,

December 13, 2022